Heat Transfer Mechanism in Thermal Conductive Materials: From Atomic Electron Motion to Macroscopic Heat Conduction

Thermal management is central to power semiconductor design, where efficient thermal structure design and material selection directly impact product competitiveness.

Analyzing the fundamental nature of heat in power semiconductors at the atomic and electronic levels reveals that beyond material properties, the “bonding” process plays a critical role.

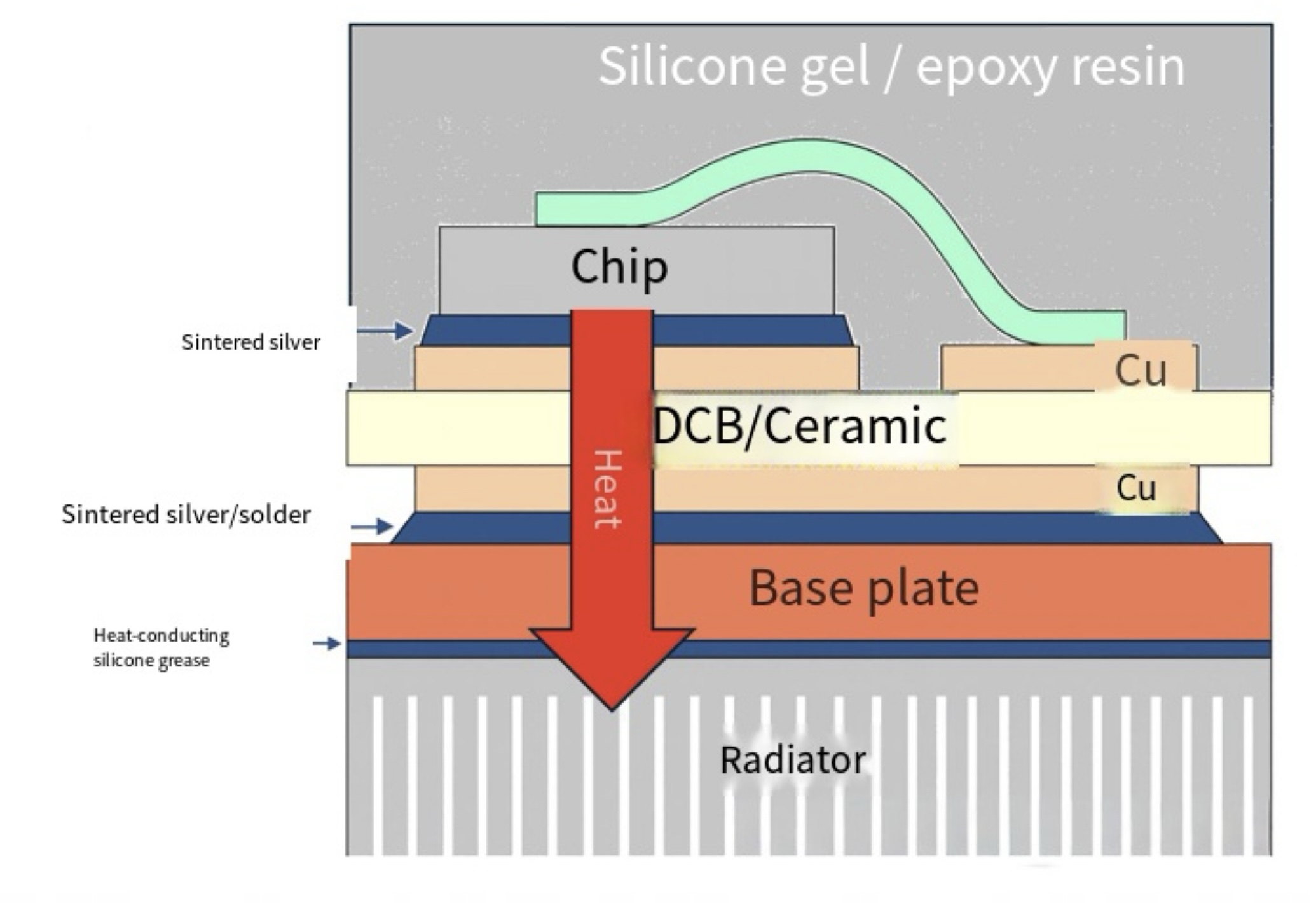

The structure of a typical power module is as follows: During operation, the chip generates significant heat, which is sequentially transferred through sintered silver and the DBC substrate to the baseplate. From there, it is conducted to the heat sink via thermal grease. Each material along this thermal path directly impacts the overall heat dissipation performance. While the market offers an extensive array of material options, experimentally validating each one would be extremely inefficient.

I. The Microscopic Essence of Heat Transfer: The Journey of Electrons and Phonons

The macroscopic phenomenon of heat conduction is fundamentally a directed migration process of energy carriers at the microscopic level. Depending on whether freely mobile electrons exist within a material, heat transfer mechanisms primarily fall into two dominant modes: electron conduction and phonon conduction. This directly determines the hierarchy of a material's thermal conductivity.

Heat Conduction in Metals: High-Speed Transport by Free Electrons

Metal atoms form highly ordered crystal structures through metallic bonds. Their outermost electrons break free from individual atoms, forming a “free electron cloud” that moves freely throughout the lattice. The microscopic essence of heat is the random thermal motion energy of particles (atoms, molecules, electrons). When one end of a metal is heated, the kinetic energy of free electrons in that region increases dramatically. These high-energy free electrons act as highly efficient “energy couriers,” traversing the lattice interstices at high speeds. Through frequent collisions with lattice atoms and other electrons, they rapidly transfer energy to the cooler end of the material. This heat transfer mechanism, based on free electron migration, is extremely efficient. Consequently, most metallic materials, such as silver, copper, and aluminum, exhibit outstanding thermal conductivity.

Heat Conduction in Non-Metals: Collective Oscillations of the Lattice

For most non-metallic materials—including ceramics, polymers, and conventional thermal interface materials—atoms or molecules are tightly bound by covalent, ionic, or van der Waals forces. These materials lack freely mobile electron carriers. Atoms or molecules are relatively fixed near equilibrium positions within the lattice, capable only of thermal vibrations. When one end of the material is heated, atomic vibrations intensify at that point. This enhanced vibration propagates sequentially through chemical bonds or intermolecular forces, like dominoes, coupling and transferring to adjacent atoms. This creates a collective vibrational wave propagating through the lattice, known as a “lattice wave” or the quasiparticle “phonon.” The efficiency of heat transfer via phonons is significantly influenced by the strength of interatomic bonds, lattice integrity, and phonon scattering. Typically, this efficiency is far lower than that of electron conduction, which is the fundamental reason for the generally low thermal conductivity of non-metallic materials.

II. Graphene: The Ultimate Example of Two-Dimensional Phonon Heat Transfer

The emergence of graphene shattered the conventional belief that “non-metallic materials must inherently conduct heat worse than metals,” demonstrating the ultimate performance achievable by the phonon heat transfer mechanism under ideal structural conditions.

Atomic Structure and Heat Transfer Principles

Graphene consists of a single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a two-dimensional honeycomb lattice through sp² hybridized bonding. Each carbon atom forms three high-strength covalent bonds with neighboring atoms, creating a perfect planar covalent network. This structure contains no free electrons, making heat transfer entirely phonon-dominated.

Structural Roots of Ultra-High Thermal Conductivity

Graphene's extraordinary thermal conductivity stems from its unique two-dimensional atomic structure, which optimizes phonon transport to the extreme. First, the highly intact, defect-free hexagonal lattice provides a nearly scattering-free “highway” for phonon propagation. Second, the exceptionally strong carbon-carbon covalent bonds ensure minimal energy loss during interatomic vibration transfer. Most critically, its single-atom thickness confines phonon propagation strictly within the two-dimensional plane, preventing energy dissipation in the vertical direction and enabling highly directional and concentrated heat flow. The synergistic effect of these factors elevates graphene's in-plane thermal conductivity far beyond most metals, establishing it as the performance benchmark for fundamental thermal materials.

III. Advanced Composites: Mechanism Integration and Engineering Challenges

Integrating graphene's high thermal conductivity with the processability and mechanical properties of traditional materials represents a key direction for developing next-generation high-efficiency heat spreaders. However, differences in microthermal mechanisms and macroscopic physical properties between materials present new scientific and engineering challenges.

Graphene-Metal Thin Film Composite Heat Spreaders

These materials aim to integrate graphene's ultra-high in-plane thermal conductivity with the process toughness and vertical heat diffusion capability of metals (e.g., copper, aluminum). Core challenges stem from the fundamental differences in heat transfer mechanisms and physical properties between the two materials:

Interface and Internal Stress Issues: Significant differences in thermal expansion coefficients between metal and graphene generate interfacial shear stresses during thermal cycling, leading to delamination failure and severely hindering heat flux transfer across the interface.

Processing Bottlenecks: Achieving robust bonding between metal atoms and graphene lattices is technically critical. Relying solely on physical adsorption (e.g., certain sputtering processes) results in high interfacial thermal resistance and weak bonding, prone to failure under vibration or thermal shock. Establishing stable, low-resistance interfaces requires complex and costly fabrication techniques.

Anisotropy Constraints: Graphene inherently exhibits poor thermal conductivity in the perpendicular direction. Even when combined with metals, improving the overall vertical thermal performance of the composite structure remains challenging. Oxidation and corrosion of metal films during long-term use also compromise reliability.

Graphite-Aluminum Composite Heat Spreader

This system employs natural graphite or highly oriented pyrolytic graphite (HOPG) bonded to an aluminum substrate, representing a more mature engineering solution. Its advantages include:

Mechanism Complementarity and Performance Balance: Graphite's high in-plane thermal conductivity combines with aluminum's superior overall thermal conductivity and mechanical properties, delivering balanced heat dissipation and structural support.

Lightweighting and Cost Efficiency: Achieves lightweight design while maintaining excellent thermal performance. Production costs offer significant advantages for large-scale application compared to cutting-edge nanomaterials.

Performance Data Validation: Under 40W heat source conditions, simulation and actual measurement data for graphite-aluminum composite heat spreaders demonstrate consistent thermal uniformity performance, significantly outperforming pure aluminum materials. Through continuous iteration, the latest product achieves approximately 40% performance improvement over previous iterations.

IV. Graphene Composite Gasket: Stability Design and Longevity Assurance

Incorporating graphene as a functional filler into polymer matrices (such as silicone) yields high-performance thermal interface materials. Their heat transfer mechanism combines phonon-mediated heat transfer (through the graphene network) with polymer chain vibration-based heat transfer. To ensure long-term reliability, the material undergoes cross-linking curing to form a three-dimensional network structure. This process stabilizes the gasket shape, enhances creep resistance, and maintains structural integrity.

Such cross-linked graphene composite gaskets achieve a design lifespan of 8 to 10 years under standard operating conditions. Key engineering measures to extend their effective service life include: strictly controlling operating temperatures to avoid prolonged exposure above the maximum temperature rating, with a recommended 10%-20% temperature margin; optimizing installation techniques to ensure flat contact surfaces and uniform pressure distribution, thereby reducing interfacial thermal resistance and localized stresses; and implementing protective designs in harsh environments to shield material interfaces from moisture and corrosive media.

www.zesongmaterial.com

Zesong